Sunday, March 17, 2013

Tragic Assault on St. Andrews Bay 20 March 1863

On 20 March 1863, a landing party from the USS Roebuck landed on St. Andrews Bay, near present-day Panama City. Their objective was to attempt to cut out a potential blockade runner. Acting Master John Sherrill, commanding the Roebuck, received intelligence that a ship was loading cotton to run the blockade. He sent a ship’s boat with 11 men, under the command of Acting Master James Folger, to proceed up the bay to find and destroy or capture the runner. Unfortunately, the landing party ran into a strong defense by Confederate home guard militia, under the command of Capt. W. J. Robinson of the C.S. Army. Seamen Thomas King and Ralph B. Snow were killed in this action and seven other sailors were injured, including the landing party commander, Act. Master Folger. The ORN reports indicate that some of the injured were "severly injured", so perhaps they died later, accounting for the listing of "six dead" on the historic marker. Capt. Sherrill’s squadron commander, Adm. Theodorus Bailey, did not approve of this action, and believed it to be “ill-advised”.

Monday, March 11, 2013

Union's Desperate Gambit to Stymie Rebel Ram Buying in Great Britain

John Murray Forbes, left, and William H. Aspinwall were given millions of dollars to outbid the Confederacy for the two rams being built at the Laird Shipyard in Birkenhead in Great Britain. (Forbes picture from Harvard Square Library. org and Aspinwall picture from Panama Rail. org)

John Murray

Forbes was feeling “half ill” and trying to rest in his Milton, Massachusetts,

home on Saturday March 14, 1863. But resting

was soon out of the question when the railroad magnate and a member of one of

New England’s leading maritime families received a “brief telegram” from

Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase. The secretary wanted to meet with him the

next day at the Fifth Avenue Hotel in Manhattan. Forbes, a man who once served

tea to John Brown, “could not refuse” and hurried to New York.

Without being explicitly told why the meeting was on such short notice, he

likely knew it concerned frightening reports on Confederate buying of advanced,

powerful warships in Europe.

With Chase, an

ardent abolitionist, that day was Navy Secretary Gideon Welles, the founder of

Hartford, Connecticut, Evening Press, and the New York-based William H.

Aspinwall, the owner of the lucrative gold-hauling Pacific Mail Steamship

Company and the builder of the trans-Panama railroad.

While not

friends, the four were acquainted with each other. Forbes and Aspinwall came from tightly-knit

Yankee families that pioneered America’s China trade of tea, silk, and opium. Welles

and Forbes met each other during the ill-fated Peace Convention in Washington

in early 1861. That winter, Aspinwall

had been in Washington discussing a plan with the Buchanan administration and

the incoming Lincoln administration to relieve Fort Sumter. He met Forbes then.

(1)

When war came

in April, Forbes peppered Chase with ideas on how to finance the conflict. His

suggestions on taxes and long-and short-term bonds, and short-term Treasury

notes for unexpected expenses, were largely ignored. Aspinwall fired off his

missives on graft in Navy acquisition to Welles and the energetic Gustavus V.

Fox, assistant secretary, with little effect

But Welles, on

the other hand, used both men to launch the Navy’s war against the Confederacy. They were in the front ranks chartering and

buying steamers to blockade Southern ports and to chase down Confederate

commerce raiders.

On their own, Forbes,

staunch Republican, and Aspinwall, long-time admirer of the cashiered George

McClellan, rallied men like themselves

into Union Leagues to back the war effort – politically and economically. They

also launched Loyal Publication Societies to boost the Union cause. Forbes also

threw himself into raising volunteer regiments in Massachusetts, including

black troops. Certainly, three of the men in the room – Welles, Forbes, and

Aspinwall – saw the United States as a naval power, but one facing the gravest

threat in its history from the sea. The fourth man, Chase, had the money to

eliminate that threat, the Confederate European shopping spree for oceangoing

ironclads.

As Fox wrote

to Forbes, “We have not a port in the North that can resist an ironclad over

very moderate power.” (2)

The Union Navy

had escaped disaster in Hampton Roads the year before when John Ericsson’s Monitor stalemated the iron-plated,

slant-roofed CSS Virginia. They won

reprieves later that spring when CSS

Virginia was scuttled because its draft was too deep to make it safely to

Richmond, and Captain David Farragut’s flotilla rushed past the still

unfinished ironclads on the Mississippi River to capture the Confederacy’s

busiest port and largest city New Orleans.

A desperate

Congress authorized letters of marque to seize blockade runners bringing war

materiel to the South. Even as the blockade tightened, Ulysses Grant marveled

at the quality and quantity of the European-made rifles the Confederates

carried at Vicksburg. But letters of marque

were worthless pieces of paper in keeping European-built ironclads taking to

sea for the South. (3)

The Union Army

fared even worse on the land. The summertime fears of Washington under siege

for the second time in two years had been palpable. After Second Manassas, “the rebels again look upon the dome of the

Capitol,” and the fears barely ebbed after the Battle of Antietam. Robert E.

Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia were still in fighting form. The two politically-driven,

grand Union advances launched in early winter had faltered. The Army of the

Potomac was again in disarray following the fiasco at Fredericksburg in

December. The Army of the Cumberland had

held its own a little later that month at Stones River in Tennessee, but with

enormous casualties.

The war

weariness in the North that cost the Republicans a number of governorships and

reduced their ranks in Congress was contagious.

Changing war

aims from restoring the Union, an ideal that Aspinwall embraced, to freeing the

slaves in states in rebellion, an ideal that Forbes blessed, proved more

popular in Europe than in many parts of the North. More fodder for the

opposition. Democrats rubbed their hands together in anticipation of the 1864

elections.

The historian

Charles Francis Adams Jr. characterized that time as “that darkest hour before

the slowly breaking dawn” of Union victories as Vicksburg and Gettysburg. (4)

Now with the

military campaign season on land fast approaching and with each arriving

steamer and mail packet from Great Britain delivering more disturbing news

about Confederate successes in building commerce raiders – like Alabama and Florida and frightening reports from Liverpool of mysterious

activities at the innovative Laird Brothers shipyard, the four agreed these

were desperate times requiring bold actions.

Before the

meeting Forbes had suggested to Fox that the United States should do everything

in its power to buy these new Laird ironclads at Birkenhead. In Forbes’ scheme,

the move would be made by a “merchant untrammeled by naval constructors and

such nuisance” in the name of “Siam or China.” Subterfuge and false fronts

were how the Confederates’ did it, why

not take a play out of their book? (5)

In Washington,

Fox liked the idea. Thinking along the same lines in London was the United

States consul Freeman H. Morse. His

subterfuges and fronts would be “Russian, Italian or other foreign houses.” Morse

proved invaluable as events were soon to show. (6)

Although Chase

paid scant heed to Forbes’ ideas on financing the war, he and Welles let the

two businessmen come up with their own statement of purpose of what they were

to do with the $10 million set aside for this effort. Their primary target was “the most dangerous

vessels,” the Birkenhead rams, the men agreed. The second point was to do this as

surreptitiously as possible. Don’t

compromise the administration or Charles Francis Adams, the American minister

in London and Forbes’ longtime friend, in the effort “to prevent the sailing of

Confederate ships.” The “deniability” approach did not apply to Morse and his

counterpart in Liverpool, Thomas Haines Dudley. The men on the scene were integral to the plan as it was sketched

out in the hotel room and as it evolved in Europe. (7)

Mr. Aspinwall

and Mr. Forbes were heading into the war.

End Notes

1. Thomas

H. O’Connor, Civil War Boston: Homefront and Battlefield, Northeastern

University Press, Boston, 1999, p. 47.

2. John Murray Forbes, Drawing on Letters and

Recollections of John Murray Forbes edited by his daughter Sarah Forbes Hughes

(hereafter Hughes, Recollections), Vol. 1, Cambridge, Google e-Book, pp. 293,

342 and Vol. 2, p. 3. John Launtz Larson, Bonds of Enterprise: John Murray

Forbes and Western Development in America’s Railway Age (hereafter Larson,

Bonds of Enterprise), Google e-Book, pp. 96-97.

3. Ulysses Simpson Grant, Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant,

Dover Publications, New York, 1995, p. 229.

4. Douglas H. Maynard, “The Forbes-Aspinwall Mission”

(hereafter Maynard, Forbes),The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, vol. 45,

No. 1 June 1958, pp. 67-89. Charles

Adams, Studies Military and Diplomatic, 1775 – 1865 (hereafter Adams, Studies),

MacMillan Company, New York, 1911, pp. 355-363.

5. Hughes, Recollections, Vol. 2, p. 27.

6. Maynard, Forbes, pp. 67-89.

7. Ibid.

Prepared Remarks of SECNAV Mabus; Video Links Posted

Secretary of the Navy Ray Mabus

Remarks

as Prepared

I’d like

to begin by acknowledging the family members who made a special trip to join

us. As the families of USS Monitor’s crew you know, as all Sailors

know, that the crew of a warship is a lot like an extended family. We thank you for being with us today to help

us honor the two Sailors we inter today, and the 14 others who perished so long

ago aboard the Monitor.

But in a

larger sense, this ceremony also honors every individual who ever put to sea in

defense of our country. From the

Marblehead men who rowed Washington across the Delaware, to these brave souls,

to those who serve today in nuclear-powered carriers and submarines, Sailors

have always been the same; they are at heart risk-takers—willing, even eager,

to brave the unknown to peer past distant horizons.

It is

fitting that we hold this ceremony today on the 151st anniversary of the Battle

of Hampton Roads, where the Monitor

engaged the Virginia for control of

the James River and Southern Chesapeake Bay. Though the outcome that day was a

draw, the battle enshrined each ship in naval immortality. As our guest James McPherson wrote in his

book War on the Waters, “Naval

warfare would never again be the same after history’s first battle between

ironclads.”

Nine

months later, Monitor ended her

short, storied career. South of Cape

Hatteras, in the area known as the graveyard of the Atlantic, Monitor and USS Rhode Island were swept up in a perilous winter gale. As the night of December 30, 1862, progressed

and the storm worsened, Monitor began

to take on water. As her pumps failed

the 62-man crew decided it was time to abandon ship. William Keeler, one of the 46 survivors,

wrote to his wife once safely ashore saying, “The heavy seas rolled over our

bow, dashing against the pilot house, and, surging aft, [and] would strike the

solid turret with a force that would make it tremble . . . Words cannot depict

the agony of those moments as our little company gathered on top of the turret

. . . with a mass of sinking iron beneath us.”

Crews from Rhode Island ventured

into the storm in their lifeboats to save the men of Monitor, Sailors struggling to save other Sailors. At one o’clock in the morning, in the pouring

rain and pitch black darkness, Monitor

slipped below the raging seas. Sixteen

men went with her.

Naval

tradition holds that the site of a sunken vessel is a sacred burial ground, and

that Sailors who go down with their ships belong together. But eleven years ago, when a team from the

U.S. Navy, NOAA, and the Mariner’s Museum in Newport News raised the turret of

USS Monitor from the depths, they

were surprised to the remains of two crew members. We began the process to try and identify

these men, but too much time had passed to match these two Sailors to their

names.

However,

having raised their remains, we brought them here, to the national military

cemetery founded during the same great conflict for which they gave, in

President Lincoln’s words, their “last full measure of devotion,” to provide

these two Sailors with a final resting place.

This may

well be the last time we bury Navy personnel who fought in the Civil War at

Arlington. But we do not hesitate to keep faith and to honor this tradition,

even more than 150 years after the promise was made. Our nation honors our fallen Sailors,

Soldiers, Airmen, Marines and Coast Guardsmen because we do not want their

sacrifice, however distant, to be unremembered.

We are joined, as Lincoln again reminded us, by “the mystic chords of

memory, stretching from every battlefield, and patriot grave, to every living

heart and hearthstone.”

In a

coincidence of history, today also marks the 124th anniversary of the death of Monitor’s designer, Swedish-American

inventor John Ericsson. The Monitor was a brand new type of ship,

all steel construction; with heavy armor, heavy guns in a rotating turret, a

deck barely above the waterline and screw propeller. Ericsson’s design was yet another example of

American naval innovation, from Joshua Humphrey’s Fast Frigates, to the Monitor, to the ships of today, the most

complex platforms the world has ever known.

As it was in Ericsson’s time, so has it always been in the Navy:

pioneering new materials, revolutionary weapons, innovative means of

propulsion, creating a technological edge we maintain to this day.

On,

above, and below the sea, our United States Sailors have always braved great

danger. In times of peace, as in times

of war, it is a dangerous profession.

Today is a tribute to all the men and women of the sea, but especially

those who made the ultimate sacrifice on our behalf, and an opportunity to once

again pay our respects and offer our somber and deeply held gratitude for that

sacrifice.

Thank you.

VIDEO LINKS:

For those of you who were unable to attend the ceremony, CHINFO has released a short video of the Chapel Ceremony. You can view it on Youtube or stream it here on this blog:

Interview with Lee Duckworth, HRNM Director of Education:

A special thanks to LT Lauryn Dempsey and CHINFO for coordinating the news media/PR for this event.

Saturday, March 9, 2013

USS Monitor Sailors Laid to Rest at Arlington National Cemetery

"O hear us when we cry to thee,

for those in peril on the sea."

- Naval Hymn "Eternal Father"

The weather was cold and dreary, but spirits were high. Amidst the machine-gun snapping of photographers, two of the "Monitor Boys" were laid to rest yesterday. Family members of Monitor sailors sat solemnly in front of the caskets as the burial detail gave the men full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery. It was a fitting conclusion to a story heard by countless people around the world. Staff members of the Hampton Roads Naval Museum/Civil War Navy Sesquicentennial and the Naval History and Heritage Command were in Arlington yesterday to take part in the events surrounding the burial of these brave men who went down with their ship over 150 years ago.

During the trek up to Washington, I received several emails from the Command PAO about an opportunity for HRNM staff to participate in the U.S. Navy's first ever Google+ Hangout. Naturally, I accepted. Looking at my car's clock just outside of Richmond, it was 10:30am. I could make it. Let the traffic gods be merciful on me today, even if it I was heading towards the "lion's den" of vehicular congestion.

|

| Google+ Hangout Session at Fort Myer |

A very special thanks to Sandy Gall at CHINFO and Junior at Google for making the event possible.

|

| Ceremony Invitation and Program |

The ceremony was both somber and reflective. Church organs bellowed "Amazing Grace" and the Naval Hymn, "Eternal Father, Strong to Save." In the corner of my eye, I could see some family members wiping tears from their eyes. It was a funeral service after all, even if those being interred died more than a century ago. To the family members present, the two men just feet in front of them could be the missing branch on their family tree. Even with the help of modern scientific technology, it is too early to tell who exactly these men were.

|

SECNAV Mabus speaks at the Chapel Ceremony (U.S. Navy photo)

|

"From the Marblehead men who rowed Washington across the Delaware, to these brave souls, to those who serve today in nuclear-powered carriers and submarines, Sailors have always been the same; they are at heart risk-takers, willing -- even eager -- to brave the unknown to peer past distant horizons." - The Honorable Ray MabusAs the ceremony concluded, guests filed behind the funeral cassions to make the quarter mile trek from the chapel to their final resting place, nestled between the mast of the Maine and the memorial to the space shuttles Columbia and Challenger.

Unfortunately, I could not get a clear view of the proceedings of the burial. The wind was blowing quite hard at this point. The Chaplain's words flickered in and out of earshot. What was heard were words of peace and hope. Words of love and devotion to one's country; concepts not lost on today's modern Navy.

Standing around me were many of the men and women who helped make this event possible. A "who's who" of naval history and maritime archaeology flanked my periphery. I could see a calmness and intensity in their eyes as the sailors eloquently folded the United States flag to a hushed crowd of hundreds. As soon as it came, the ceremony was over.

Mariners' Museum VP of Museum Collections Anna Holloway was one such individual who played a huge role in bringing those men to Arlington. Looking away from the ceremony, Holloway smiled with satisfaction. "We did it," she said, smiling with delight. Her words likely reflected the sentiment of many there standing in our nation's most hallowed ground. For our good friends at the Mariners' Museum and USS Monitor Marine Sanctuary, yesterday marks a triumphant end to over a decade of hard work.

It was not only the Battle OF Hampton Roads, it was also a Battle FOR Hampton Roads. For the security of our nation. For the preservation of the Union and the thousands of men who gave the ultimate price to protect it. The Monitor stands as a symbol of honor, courage, and commitment resonating still today. Their final measure of devotion was honored gloriously.

I was happy to be there and take part in the event. It was truly a once in a lifetime experience that I will never forget.

As Chaplin Glore stated in the closing remarks of the chapel ceremony, the event gives "new energy to the past and present" history of Monitor and the men that fought beneath her iron decks and rotating turret.

Rest easy, Monitor Boys. Your voyage is finally over.

Relevant Links to Yesterday's Ceremony:

Navy.mil News Story

SECNAV Photos

CBS News Story on USS Monitor

Washington Post (Excellent Photo Gallery)

Baltimore Sun

NOAA

NPR

USS Monitor Twitter Stream

NHHC Documents on the Battle of Hampton Roads

Friday, March 1, 2013

Ironclads on the Georgia Coast - Monitor vs. Fort II

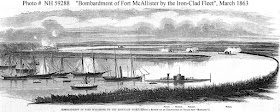

Ironclads USS Passaic, Patapsco and Nahant bombarding Ft. McAllister. Note monitor Montauk hanging back with the wooden gunboats.

Admiral S. F. DuPont was determined to take out Ft.

McAllister, guarding the entrance to the Ogeechee River, Georgia. He decided

that if one monitor could not do it, he would send in three, accompanied by

other gunboats. He sent the USS Passaic,

Patapsco, and Nahant (under the overall command of Capt. Percival Drayton of the Passaic). All three were the newer Passaic Class of ironclad monitor

gunboats. Passaic and Nahant were armed with XV and XI inch

Dahlgren guns. Patapsco had a XV inch

Dahlgren and a 200 pdr Parrott rifle. Each gunboat was painted in a different

color scheme so they could identify one another. Capt. John Worden in the USS Montauk (another Passaic Class monitor) went along as a supporting vessel, but was

ordered by DuPont to avoid action. There was concern that Montauk’s XV inch Dahlgren might be close to the end of its

lifespan, because it had already been fired almost 300 times in the prior

engagements. DuPont wanted to spare Montauk

for use in the upcoming attack on Charleston harbor.

The morning of 3 March 1863, the four turreted ironclads,

accompanied by the wooden gunboats Seneca,

Dawn, Wissahickon, Flambeau,

and Sabago and the mortar schooners C. P. Williams, Norfolk Packet and Para (towed

by a steam tug) got steam up and headed up the river towards the fort. The

mortar schooners were placed and the three new monitors approached the confederate

fort. The fort had recently received some additional heavy guns and its

garrison watched the approaching ironclads, ready to use them. About 8:30 AM

Ft. McAllister opened fire, initiating the third “ironclad vs. fort”

engagement. The Union gunboats returned fire. The gunners in the fort knew by

now they couldn’t damage or sink the ironclads just by hitting them. They

waited until the turrets of the monitors turned to fire at the fort and tried

to aim for the open gunports, hoping a lucky shot would go through.

The firefight continued all that morning and into the

afternoon. The fort scored numerous hits on the ironclads (mostly concentrating

on Passaic), and the naval gunnery

burst around and within the fort. A number of the larger confederate guns were

disabled by shots from the ironclads. During the fight, Drayton stepped out

onto the top of Passaic’s turret with

his telescope to survey the scene. Suddenly musket balls went whizzing by, and

he was hit, but uninjured, by an apparent ricochet. Prior to the battle, a

squad of sharpshooters had been sent out from the fort, under the command of CSA

Lt. Elijah Ellarbee, to establish an outpost to try to pick off USN gunners

through the open gunports of the monitors’ turrets as they turned away from the

fort to reload. They were so close to the Passaic

that Ellarbee later said he could hear the orders of the gun captains to the crews

in the turret as they went through their drill.

By mid-afternoon, about 3:30, Drayton ordered

the flotilla to withdraw due to the falling tide. The three mortar schooners

were left to continue lobbing shells at the fort in hopes of interfering with

repair efforts. Both Passaic and Nahant experienced mechanical problems

during the battle. When he surveyed the damage to his ship after the fight,

Drayton noted that Passaic seemed to

suffer much more damage to her armor than did Montauk in her prior two engagements with the fort, apparently due

to deficiencies in the bolts used to anchor the iron plating and problems with

the iron itself. DuPont ordered the installation of an additional layer of iron

plating on the decks of the monitors. As would become evident in the upcoming

attack on Charleston, the monitor gunboats simply could not bring to bear the

overwhelming firepower that a “broadside” type warship could, and that this is

what was needed to defeat shore fortifications.

USS Passaic. Source of images - Naval History and Heritage Command.

Confederate Ironclads Attack the Charleston Blockade

|

| CSS Palmetto State |

The U.S.N's blockade nearest to Charleston's forts had only two wooden gunboats: USS Keystone State and Mercedita. The Confederate ironclads put to sea at 11:30 p.m. and, due to their slow speed, reached the U.S.N's patrol lines at 4:30 the next morning. Both the dark night and a heavy fog assisted the ironclads in achieving the element of surprise.

|

| Palmetto State rams Mercedita and Keystone State and Chicora exchange shots. |

|

| USS Keystone State |

Fortunately for Keystone State, time was against the Confederates. As daylight appeared, other ships of the blockading squadron, specifically USS Housatonic, Augusta, Memphis, Flag, and Quaker City rushed to the scene of battle. Also as the sun rose, the tide ebbed. Fearing that he would not get his ships back across the sand bar at the entrance to Charleston Harbor, Ingraham decided to call off the attack. As the ironclads withdrew, Housatonic took a shot at Palmetto State and knocked off her smoke stack. The battle was over.

As the Union pulled back to repair their ships and remove casualties, General Beauregard and Ingraham immediately wrote letters to every foreign consulate to proclaim the blockade at Charleston had been risen (which would have forced the U.S. Navy to reissue a new blockade proclamation and keep the port open for 72 hours). At first the English, French, and Spanish diplomats agreed. But upon seeing the arrival of USS New Ironsides and other ships just a day later, the British consulate, Frederick Milnes Edge, changed his mind. He personally apologized to Admiral DuPont for his hasty declaration and wrote that it was his new opinion that the blockade at Charleston was still in force.