One of the things they have taken up recently is kick-starting a new program here at HRNM, Brick by Brick: LEGO Shipbuilding. How does this relate to the CWN 150? One of the models that will be available to build for this program is the USS Monitor created by intern Samuel Nelson (shown here).

Saturday, July 30, 2011

LEGO USS Monitor Model at HRNM

As many of you know, the headquarters for the Civil War Navy Sesquicentennial is at the Hampton Roads Naval Museum. As an educator at the museum itself, one of the tasks assigned to our staff is to hire summertime interns who work in coordination with the education department. This summer, we seemed to have struck paydirt. Our two HRNM interns, Samuel Nelson and Jordan Hock, have done a phenemonal job this summer with the creation and execution of various programs, including the debut of the first CWN 150 program Blockade: The Anaconda Plan (Available Soon).

One of the things they have taken up recently is kick-starting a new program here at HRNM, Brick by Brick: LEGO Shipbuilding. How does this relate to the CWN 150? One of the models that will be available to build for this program is the USS Monitor created by intern Samuel Nelson (shown here).

You can read the full blog post on the shipbuilding program on the HRNM Blog HERE.

One of the things they have taken up recently is kick-starting a new program here at HRNM, Brick by Brick: LEGO Shipbuilding. How does this relate to the CWN 150? One of the models that will be available to build for this program is the USS Monitor created by intern Samuel Nelson (shown here).

Friday, July 29, 2011

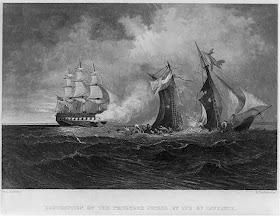

July 28, 1861-An Elephant Squashing a Gnat-USS St. Lawrence v. Privateer Petrel

A few hours into the deployment, Petrel's company spotted what it thought was its first catch. It was a large ship, according to the watches, specifically it looked like a large East Indiaman-type merchant ship. As the two ships closed range, watches on Petrel realized they had made a horrible mistake. The ship was not a merchant, but rather a U.S. Navy frigate.

Petrel's captain turned the ship about and attempted to escape. The company then made a second mistake, they fired at the frigate and put a shot through one of the frigate's sails. This only succeeded making the frigate angry. The frigate returned fire several times with her forecastle gun, an 8-inch shell gun.

The warship was the sail frigate USS St. Lawrence. Displacing 1,726 tons and carrying over fifty guns (vs. Petrel's 86-tons and two guns), the engagement is one of the greatest mismatches in world naval history (possibly only matched by the battleship HMS Dreadnought ramming the submarine U-29 in 1915). At least one shell from St. Lawrence struck Petrel and exploded. Small boats from St. Lawrence were deployed and rescued thirty-six of the thirty-eight man company (two drowned).

The victory was over-hyped in Northern press as an example of how easy the war at sea was going to be for Federal forces. The New York Times, for example, ran the headline "The Perils of Privateering." Petrel's company was taken to Philadelphia for adjudication on board USS Flag.

Saturday, July 23, 2011

The Steam Screw Frigates

When it comes to the Civil War Navies (really, any Navy), no doubt one of the main “stars of the show” are the ships. Over the past year, we of the CWN150 have enjoyed introducing you to some of the ships of the US Navy in the Civil War, including the “Timberclads” (posts by Craig on 22 Sept 2010 and Caleb on 16 June 2011), the “90-day gunboats” (post by Gordon on 12 July 2011), and the “fighting ferryboats” (post by yours truly on 14 Oct 2010). In time, we will also present overviews of the ships of the Confederate Navy.

The largest class of warships in the US Navy in the war were the “Merrimack” class steam screw frigates. These warships were propelled by a combination of sail (square-rigged) and steam power and were the first US Navy ships to be driven by a “screw” (a propeller on a shaft projecting through the stern). They displaced 3,000+ to 4,000+ tons and ranged in length from 256’10.5” to 264’8.5”. The US Congress authorized construction of these in 1954. All were completed and commissioned before the war began. In keeping with the ship building philosophy of the US Navy (as with the Constitution-class of sailing frigates), these ships were to be larger and heavier-armed than similar ships in their class and be fast enough to outrun anything larger. The USS Merrimack, Wabash, Roanoke, and Colorado were

all named for US rivers; the Minnesota was named for the territory at the time (not yet a state). All were armed with 24 to 28 IX inch Dahlgren smoothbore shell guns on the main gun deck. These were supplemented with 8-inch shell guns in broadside and a 10-inch gun (typically mounted forward) on the spar deck.

At the time they were built, these were among the most formidable warships in the world, although they were somewhat slow (generally not able to exceed 8 knots under steam), and their deep draft proved to be a considerable handicap in the shallow inshore waters and bays of the southeastern US and Gulf coasts during the war. The Wabash saw service in the South Atlantic blockading squadron, serving as DuPont’s and Dahlgren’s flagship. The Merrimack was burned at the start of the war in the Washington Navy Yard and as we know, was resurrected as the ironclad CSS Virginia. The Minnesota was the flagship of Flag Officer Stringham in the Atlantic blockading squadron, and remained Goldsborough’s flagship when he took command of the North Atlantic blockading squadron. Both Minnesota and Roanoke were present at Hampton Roads during that first clash of the ironclads; the Minnesota was driven aground by the Virginia, which would have returned the next day to destroy her if not for the defense by USS Monitor.

The Roanoke was present offshore of Hampton Roads that day and could not enter the harbor because of her draft, although even if she did, she couldn’t have done anything to help her sister ship against the Virginia. The USS Colorado began her war service in the Gulf blockading squadron, serving off the Mississippi River and Mobile Bay; she ended the war in the North Atlantic squadron and was a participant in the assault on Fort Fisher.

A sixth ship in this class was the USS Niagra (named after Fort Niagra, captured from the British by American forces in the War of 1812). Designed by George Steers, he envisioned a warship with the lines and speed of a clipper ship and an armament comparable to the other frigates in her class. To accomplish this, he had to make her immense, displacing in excess of 5,000 tons and over 300’ in length. Despite her size, she did turn out to be a very fast ship, making 10-11 knots under steam and up to16 knots when under sail power. Initially she was armed only with weapons on her spar deck; XI inch Dahlgren guns on pivots. In the middle of the war she was refitted with twenty XI inch Dahlgrens in broadside on her main gun deck, along with the spar deck armament, but the weight of this gunnery made her main deck gunports dangerously low along the waterline and the main deck broadside guns were removed. She was a participant in two historic events prior to the war: helping to lay the first transatlantic cable and transporting the first Japanese delegation to the US back home to Japan. In the Civil War, she saw service in both Atlantic and Gulf squadrons and in the latter half of the war was deployed overseas keeping tabs on Confederate warships being constructed in European shipyards.

RESOURCES

Canney, Donald L. Lincoln’s Navy. The Ships, Men and Organization, 1861-65. London: Conway Maritime Press, 1998.

Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships: http://www.history.navy.mil/danfs/index.html

The largest class of warships in the US Navy in the war were the “Merrimack” class steam screw frigates. These warships were propelled by a combination of sail (square-rigged) and steam power and were the first US Navy ships to be driven by a “screw” (a propeller on a shaft projecting through the stern). They displaced 3,000+ to 4,000+ tons and ranged in length from 256’10.5” to 264’8.5”. The US Congress authorized construction of these in 1954. All were completed and commissioned before the war began. In keeping with the ship building philosophy of the US Navy (as with the Constitution-class of sailing frigates), these ships were to be larger and heavier-armed than similar ships in their class and be fast enough to outrun anything larger. The USS Merrimack, Wabash, Roanoke, and Colorado were

all named for US rivers; the Minnesota was named for the territory at the time (not yet a state). All were armed with 24 to 28 IX inch Dahlgren smoothbore shell guns on the main gun deck. These were supplemented with 8-inch shell guns in broadside and a 10-inch gun (typically mounted forward) on the spar deck.

At the time they were built, these were among the most formidable warships in the world, although they were somewhat slow (generally not able to exceed 8 knots under steam), and their deep draft proved to be a considerable handicap in the shallow inshore waters and bays of the southeastern US and Gulf coasts during the war. The Wabash saw service in the South Atlantic blockading squadron, serving as DuPont’s and Dahlgren’s flagship. The Merrimack was burned at the start of the war in the Washington Navy Yard and as we know, was resurrected as the ironclad CSS Virginia. The Minnesota was the flagship of Flag Officer Stringham in the Atlantic blockading squadron, and remained Goldsborough’s flagship when he took command of the North Atlantic blockading squadron. Both Minnesota and Roanoke were present at Hampton Roads during that first clash of the ironclads; the Minnesota was driven aground by the Virginia, which would have returned the next day to destroy her if not for the defense by USS Monitor.

The Roanoke was present offshore of Hampton Roads that day and could not enter the harbor because of her draft, although even if she did, she couldn’t have done anything to help her sister ship against the Virginia. The USS Colorado began her war service in the Gulf blockading squadron, serving off the Mississippi River and Mobile Bay; she ended the war in the North Atlantic squadron and was a participant in the assault on Fort Fisher.

A sixth ship in this class was the USS Niagra (named after Fort Niagra, captured from the British by American forces in the War of 1812). Designed by George Steers, he envisioned a warship with the lines and speed of a clipper ship and an armament comparable to the other frigates in her class. To accomplish this, he had to make her immense, displacing in excess of 5,000 tons and over 300’ in length. Despite her size, she did turn out to be a very fast ship, making 10-11 knots under steam and up to16 knots when under sail power. Initially she was armed only with weapons on her spar deck; XI inch Dahlgren guns on pivots. In the middle of the war she was refitted with twenty XI inch Dahlgrens in broadside on her main gun deck, along with the spar deck armament, but the weight of this gunnery made her main deck gunports dangerously low along the waterline and the main deck broadside guns were removed. She was a participant in two historic events prior to the war: helping to lay the first transatlantic cable and transporting the first Japanese delegation to the US back home to Japan. In the Civil War, she saw service in both Atlantic and Gulf squadrons and in the latter half of the war was deployed overseas keeping tabs on Confederate warships being constructed in European shipyards.

RESOURCES

Canney, Donald L. Lincoln’s Navy. The Ships, Men and Organization, 1861-65. London: Conway Maritime Press, 1998.

Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships: http://www.history.navy.mil/danfs/index.html

Thursday, July 21, 2011

Civil War at Sea: Leadership in the Civil War Video Available on Youtube

Hampton Roads Naval Museum and CWN 150 Staff have been working closely with Bob Rositzke of R.H. Rositske & Associates to create a series of educational videos discussing the role of the navies during the Civil War. We are all pleased to announce the first of five videos, "Leaders in the Civil War," is now available for viewing on Youtube. The video is sponsored by William Erickson and the Surface Navy Association.

You can go to Bob Rositzke's Youtube page HERE to view all of his videos. Stay tuned in the upcoming weeks for more videos! Please leave comments!

You can go to Bob Rositzke's Youtube page HERE to view all of his videos. Stay tuned in the upcoming weeks for more videos! Please leave comments!

Tuesday, July 19, 2011

"Drive On": The Genius of James Buchanan Eads

Building a naval fleet is not the work of a military organization alone. In the Civil War as now, the Navy depended upon businesses and individuals of action to help conceive and produce the nation's ships of war. John Ericsson traditionally receives effusive praise and a surfeit of attention for his role in designing the Monitor and a host of other ingenious creations. But Ericsson has a forgotten counterpart in the American west: James B. Eads. Without Eads's shipbuilding and design collaboration, the western ironclad flotilla may never have come into being, or its birth might have been a great deal more painful.

James Eads started, as many great figures of American history, under inauspicious circumstances. Raised in relative poverty, as a boy, Eads supported himself by working in a variety of menial capacities on commercial riverboats. His job selling apples to hungry passengers took him to the west's great ports and waterways and gave him an expert knowledge of western rivers and their unique navigational challenges.

Eads applied his experiences while still a young man, designing a primitive diving bell that allowed him to descend upon submerged wrecks and salvage their valuable cargoes. Eads achieved such great success that he went on to design and construct several purpose-built boats, which he called submarines. These unique river craft were capable of raising entire wrecks, and Eads's salvage operations had little competition. By the 1850's, Eads had earned a fortune, and he entered retirement at the age of 37.

The arrival of the Civil War brought the prominent St. Louisan out of his permanent retreat. Working with U.S. Attorney General (and Missourian) Edward Bates, Eads secured an audience with cabinet leaders in Washington. Nothing definitive resulted from this tentative spring meeting, but policy makers heard his proposals for the fortification of the upper Mississippi. Naval Constructor Pook also had the opportunity to evaluate Eads's design of an armed and front-armored riverboat. Pook saw promise in the energetic riverman's ideas. Secretary of War Simon Cameron thought the notion of a Mississippi ironclad absurd, and he axed any early construction efforts.

Undeterred, Eads followed his own motto of "Drive On" and presented new proposals to the government. Eads believed his Submarine no. 7 could be refitted and converted into a formidable warship. The Army's Navy advisors needed only approve the proposal, and the improved shallo

w-draft ship could be delivered within months. But Commander Rodgers saw no merit in converting no. 7. Military authorities would later reconsider the offer.

w-draft ship could be delivered within months. But Commander Rodgers saw no merit in converting no. 7. Military authorities would later reconsider the offer.In August 1861, the Army and Navy finally came to their senses. A few timberclads and a swarm of lightly-armed riverboats would be insufficient force to pacify the Mississippi. The war in the west demanded an ironclad gunboat fleet. In early August Eads won the bid to construct seven ironclads, all to be delivered within three months. The contract secured, and his expertise finally acknowledged, Eads rapidly plunged into work and set his shipyards to the task. The ironclads would be built in Mound City, Illinois, on the Ohio River, and at the burgeoning Mississippi river port at Carondelet, Missouri, south of St. Louis. Once completed these "Pook Turtles" or "City Class" ironclads would form the core of the Union's western naval might. Eads would continue to design and build ironclads in the west, launching the Osage and Neosho in 1862, and several more vessels later in the conflict. Eads's shipbuilding centers became some of the chief hubs of naval activity in the west, and would remain commercial centers long after the war concluded.

Eads may have been the only man capable of properly undertaking such a huge building project in far-flung territory the Union military often regarded as a side show to the big show. Certainly, the Union benefited greatly from his unceasing energy and forward-thinking action. Had the South had its own James Eads, the war for the west might have gone a great deal differently.

In upcoming posts, we'll explore the west's naval bases, including Carondelet and Mound City, where thousands of laborers built the City Class ironclads that helped win the war.

Tuesday, July 12, 2011

Building the "90-day" Gunboats

| Unadilla, Winona, and Ottawa under construction |

| William Henry Webb (left) and Jacob Aaron Westervelt (right) |

|

| Finished "90-day" gunboats |

Monday, July 4, 2011

How Did They Deal With It ??

In a prior post, I have mentioned that one of the things that most intrigues me about participating in living history events is the opportunity to experience what the “old salts” did in the Civil War. That thirst for experiences stops just a bit short of the ultimate event; naval combat (although a little piece of me still wants to know what it was like). A buddy at work is a fan of the War of 1812 Navy; both he and I have read the book “Six Frigates” by I. W. Toll, and we always ask ourselves, “How did those sailor-guys deal with the combat? How could they stand there and blast away at each other and stay sane?”

John Keegan in his book “The Price of Admiralty” makes a really interesting point. If you visit a terrestrial battlefield, there is always an element of uncertainty for the historian or history buff. Take Gettysburg (the 148th Anniversary just celebrated this past weekend): no matter how detailed your knowledge of blackpowder infantry, cavalry, or artillery tactics, you have to ask, did Buford post Calef’s battery here, or further down the road? Was Chamberlain standing here on Little Round Top when he ordered the bayonet charge, or over there? Did Lo Armisted’s brigade emerge from the woods here on Pickett’s Charge, or a hundred yards over?

Keegan goes on to note that when you set foot on a warship, many of these uncertainties vanish. Step onto the main gun deck of HMS Victory, or USS Constitution, and instantly visualize where the personalities stood; the gun division officers at their posts, the Captain on the quarter deck, the gun crews, etc. Stand beside one of the guns and peer over the barrel through the gunport; 200-some years ago, guys were doing this very same thing for real, surrounded by the crash of shot into wood, the roar of your ship’s guns, the squeal of the trucks on the deck as the guns were run out, the smoke, the screams of the wounded. On a warship, you get a much closer feel for what the experience of combat may have been like than you might visiting a battlefield.

In his book “Quarter-Deck and Fo’c’s’le”, J. M. Merrill reproduces a description of the battle between Farragut’s squadron and Forts Jackson and St. Philip on the Mississippi, as he moved upriver to take New Orleans. Written by Seaman Bartholomew Diggins, he describes the height of the battle (unedited and reproduced as published in Merrill’s book):

“The broad side guns were now in full action and ever man had all he could attend to . . . the nois and roar at this time was teroble, and cannot be described, but to help the emagination, there was over three hundred guns and morrtars of the largest calabre in full blast, double this, by the explosion of shells fired by them then add to this the hissing and crashing through the air . . . confine this in a half mile square, it may give some idea of the nois and uproar that was taking place.”

For his action in this engagement, Diggins was awarded the Medal of Honor.

Having served on gun crews now for several types of field pieces (3” ordnance rifle, a couple different calibers of mountain howitzer, and of course my favorite, a 12 pdr Dahlgren boat howitzer), I think the rhythm of the gun drill itself created almost a “hypnotic control” which kept the guys focused (the gun captain calling out the drill to the crew; “Worm”, “Sponge”, “Load”, “Run the gun out”, etc.). During the battle between the CSS Alabama and USS Kearsarge, Seaman John Bickford was on the crew manning the Kearsarge’s forward 11-inch pivot gun (Naval History, December 2010). After an extremely close miss (the passing of the shell literally took his breath away), his gun captain asked him why he didn’t try to dodge the shot. He is said to have replied “Haven’t got time, sir. I’m busy.” which seems to lend some credence to my idea.

Any folks out there with a psychology background who could lend some insight into this? It really does boggle the mind when you think about what these guys dealt with in combat (ship to ship or ship against fort).

RESOURCES

Delaney, Norman C. I Didn’t Feel Excited a Mite. Naval History: December, 2010. Pp. 36-41.

Keegan, John. The Price of Admiralty. The Evolution of Naval Warfare. New York: Viking Penguin, Inc., 1988.

Merrill, James M. Quarter-Deck and Fo’c’s’le. The Exciting Story of the Navy by the Men Who Served. Chicago: Rand McNally and Co., 1963.

John Keegan in his book “The Price of Admiralty” makes a really interesting point. If you visit a terrestrial battlefield, there is always an element of uncertainty for the historian or history buff. Take Gettysburg (the 148th Anniversary just celebrated this past weekend): no matter how detailed your knowledge of blackpowder infantry, cavalry, or artillery tactics, you have to ask, did Buford post Calef’s battery here, or further down the road? Was Chamberlain standing here on Little Round Top when he ordered the bayonet charge, or over there? Did Lo Armisted’s brigade emerge from the woods here on Pickett’s Charge, or a hundred yards over?

Keegan goes on to note that when you set foot on a warship, many of these uncertainties vanish. Step onto the main gun deck of HMS Victory, or USS Constitution, and instantly visualize where the personalities stood; the gun division officers at their posts, the Captain on the quarter deck, the gun crews, etc. Stand beside one of the guns and peer over the barrel through the gunport; 200-some years ago, guys were doing this very same thing for real, surrounded by the crash of shot into wood, the roar of your ship’s guns, the squeal of the trucks on the deck as the guns were run out, the smoke, the screams of the wounded. On a warship, you get a much closer feel for what the experience of combat may have been like than you might visiting a battlefield.

In his book “Quarter-Deck and Fo’c’s’le”, J. M. Merrill reproduces a description of the battle between Farragut’s squadron and Forts Jackson and St. Philip on the Mississippi, as he moved upriver to take New Orleans. Written by Seaman Bartholomew Diggins, he describes the height of the battle (unedited and reproduced as published in Merrill’s book):

“The broad side guns were now in full action and ever man had all he could attend to . . . the nois and roar at this time was teroble, and cannot be described, but to help the emagination, there was over three hundred guns and morrtars of the largest calabre in full blast, double this, by the explosion of shells fired by them then add to this the hissing and crashing through the air . . . confine this in a half mile square, it may give some idea of the nois and uproar that was taking place.”

For his action in this engagement, Diggins was awarded the Medal of Honor.

Having served on gun crews now for several types of field pieces (3” ordnance rifle, a couple different calibers of mountain howitzer, and of course my favorite, a 12 pdr Dahlgren boat howitzer), I think the rhythm of the gun drill itself created almost a “hypnotic control” which kept the guys focused (the gun captain calling out the drill to the crew; “Worm”, “Sponge”, “Load”, “Run the gun out”, etc.). During the battle between the CSS Alabama and USS Kearsarge, Seaman John Bickford was on the crew manning the Kearsarge’s forward 11-inch pivot gun (Naval History, December 2010). After an extremely close miss (the passing of the shell literally took his breath away), his gun captain asked him why he didn’t try to dodge the shot. He is said to have replied “Haven’t got time, sir. I’m busy.” which seems to lend some credence to my idea.

Any folks out there with a psychology background who could lend some insight into this? It really does boggle the mind when you think about what these guys dealt with in combat (ship to ship or ship against fort).

RESOURCES

Delaney, Norman C. I Didn’t Feel Excited a Mite. Naval History: December, 2010. Pp. 36-41.

Keegan, John. The Price of Admiralty. The Evolution of Naval Warfare. New York: Viking Penguin, Inc., 1988.

Merrill, James M. Quarter-Deck and Fo’c’s’le. The Exciting Story of the Navy by the Men Who Served. Chicago: Rand McNally and Co., 1963.